Phil began by talking about the international study tour which looked at cycle infrastructure in the UK, Europe and the US and some of the lessons that had been learned.

Phil Jones: “The aim is to develop a planned network”

He emphasised that it’s possible to achieve rapid results when there is strong political direction. For example in New York, a city not generally considered as a cycling city, Mayor Bloomberg made the political decision to make changes very quickly: “It came from the top.”

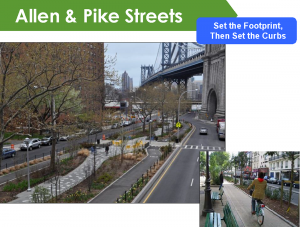

When you act quickly it releases the suppressed demand for cycling, and when people see the increase in cycling levels “it changes political views”. First they did inexpensive stuff. There was no capital funding, but with ingenuity and a determination to achieve results they used revenue funding for paint and plant pots to mark out cycle lanes. He showed how Allen and Pike Streets were transformed with temporary light segregation, which won the space for cycling as a first step towards permanent provision: “Set the footprint, then set the kerbs.”

Allen & Pike Streets: light segregation used to “set the footprint”

Phil then spoke about Copenhagen where over 60% of people cycle to school or work. He showed that this can be achieved with infrastructure that is “not particularly elegant”. It can be simple (e.g. stepped tracks) but it should be consistent and predictable so that instead of having designated ‘cycle routes’, you can just “set off in the expectation that you’ll be able to complete your journey because the infrastructure is there”.

People in Copenhagen don’t cycle to ‘save the planet’ but because it works for them – it’s convenient, quick and easy: “That’s what we have to move towards.”

In Copenhagen the priority law on turning is different to the UK: “We have to think about this”, but making improvements like those in Copenhagen does not depend on it.

TfL’s International Cycling Infrastructure Best Practice Study

The international study tour looked at the factors for success: “Leadership is essential – both political and technical.” He emphasised that while political leadership is vital, technical people have a special role in that they can provide continuity and “can see it through the fallow times” i.e. changes of political administration.

In the UK things are starting to change: “TfL as an organisation gets cycling now.”

CWIS and LCWIPs

The draft Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy (CWIS – pronounced “C-whizz”) was a bit of a disappointment – there was a lack of investment for the strategy.

Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plans (LCWIPs – pronounced “LC-whips”) have different aims for cycling and walking: for walking we already have a network (the pavements and footpaths) so the aims are different. For cycling “the aim is to develop a planned network”. Developing a high quality environment and filling in gaps in provision.

The final CWIS is due in October and Phil expects the LCWIP guidance to be introduced at the same time.

It’s important to get buy-in from the LEPs and this should be led by them where possible. There is no ring-fenced money for cycling, so the LEPs decide whether and how much to invest in cycling.

LCWIPs are scalable so you can create them for part of a city or a whole region, and across LA boundaries.

Phil considers the Propensity to Cycle Tool (PCT) to be “the engine under the bonnet” for LCWIPs: “Start with the demand, the desired routes.”

In conclusion, we need:

- Properly evidenced, long-term plans for infrastructure (e.g. using the PCTC), not opportunity-led.

- Planned networks – e.g. Copenhagen cyclists don’t need to plan their journeys: roads have cycling infrastructure.

- Rules and behaviour to support infrastructure.

- Integration with land use planning.

This would create a strong position from which to access funds.

See Phil’s presentation.

Return to the report.